Rise of China as Global Challenger

The rise of China as global challenger is captured symbolically in the image of a high-speed train — sleek, modern, and built on decades of relentless investment in infrastructure. Where the United States once stood alone at the pinnacle of world power, China now advances with speed and purpose. Its leaders insist this is not a new ascent but a return to the natural order: a restoration of a position held for much of recorded history.

How does the rise of China as global challenger unfold?

Civilizations carry long memories. For most of the past two thousand years, China was the largest economy on earth. The Han dynasty, flourishing two millennia ago, governed a sophisticated agrarian empire whose size and wealth dwarfed Rome. The Tang and Song dynasties presided over technological breakthroughs — the invention of paper, printing, the compass, and gunpowder. By 1800, on the eve of Europe’s industrial leap, China still produced nearly a third of global GDP (Maddison Project).

This dominance collapsed in what Chinese leaders still call the “Century of Humiliation”. Beginning with the Opium Wars in 1839, foreign powers pried open ports, imposed unequal treaties, and carved out spheres of influence. The Qing dynasty fell in 1911; decades of warlordism and Japanese invasion followed. By 1949, when Mao Zedong declared the founding of the People’s Republic, China was impoverished, fractured, and far removed from its historic preeminence.

How did China return to the stage?

Mao’s early rule brought social transformation but economic stagnation. The Great Leap Forward (1958–62) led to famine, and the Cultural Revolution (1966–76) fractured society. It was only with Deng Xiaoping’s reforms from 1978 that China began to open to the world. Special Economic Zones in Shenzhen and elsewhere invited foreign investment, and markets gradually took root alongside state planning.

The impact was extraordinary. China’s GDP rose from just 2% of the global total in 1990 to around 18% today (IMF DataMapper). The country became the world’s largest exporter, its factories assembling everything from shoes to smartphones. Entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001 cemented this trajectory, accelerating its integration into global supply chains.

What built its economic rise?

China’s transformation was not only about volume, but about moving up the value chain. Infrastructure investment reached unprecedented scale: high-speed rail now stretches more than 40,000 kilometers, and cities that were once provincial towns became megacities. By 2019, China accounted for 28.7% of global manufacturing output, compared to 16.8% for the U.S. (USITC).

Technology catch-up has accelerated. Companies like Huawei and BYD lead in 5G and electric vehicles; TSMC in neighboring Taiwan depends on Chinese markets. The semiconductor sector has become a flashpoint. U.S. export restrictions on advanced lithography equipment, such as ASML’s EUV machines, were meant to cap Beijing’s progress. Instead, Chinese firms redirected resources into indigenous chipmaking, advancing capabilities in mature nodes and developing alternative lithography pathways.

Resource control is another pillar. China refines nearly 90% of the world’s rare earths, essential for magnets used in everything from smartphones to fighter jets (USGS). It is also the world’s largest gold producer, with output reinforcing both its central bank reserves and its broader strategy of diversifying away from U.S. Treasuries (Reuters). In agriculture, Beijing leverages consumption as a geopolitical tool: withholding soybean orders from American farmers when tariff disputes flare illustrates how food imports can be wielded as leverage.

How does China project power today?

The rise is not just economic. China has transformed its military from a “people’s army” into a modern force. A blue-water navy now challenges U.S. dominance in the Pacific. Hypersonic missile tests and space programs underscore ambition.

Equally important is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Through trillions of dollars in loans and construction projects, Beijing has financed ports, railways, and energy infrastructure across Asia, Africa, and Latin America. This investment brings not just soft power but leverage. When China owns the port or the power grid, it gains both economic influence and a justification for defending those interests militarily if challenged.

China is also reshaping institutions. It anchors the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, funds the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, and drives the expansion of BRICS, which now accounts for nearly half the world’s population and 40% of global GDP in PPP terms (IMF). Beijing presents itself to the Global South as a patient, long-term partner — contrasting its investments with Western conditionality and using this base of support to secure diplomatic alignment in multilateral forums.

What strains accompany this ascent?

Challenges remain in the rise of China as global challenger. China faces a shrinking workforce and rapidly aging population. Debt from years of infrastructure building weighs on local governments. Political rigidity and censorship stifle dissent, while issues in Xinjiang and Hong Kong have drawn international criticism. Energy and food imports expose vulnerabilities, and foreign governments increasingly resist Chinese investment. Export controls, such as U.S. restrictions on advanced semiconductors, highlight the pushback Beijing faces.

Where does China stand in 2025?

Measured in nominal terms, China’s economy now stands at around $18 trillion, nearly 18% of global GDP (World Bank). In PPP terms, it is already the largest. It is the world’s leading exporter, its companies dominate clean energy supply chains, and its military modernization continues at pace.

The renminbi (RMB) has begun to emerge as a reserve currency. Central banks have steadily increased holdings, and China has rotated out of U.S. Treasuries into gold. A year ago, the idea of the RMB as a reserve currency seemed remote; today it looks almost inevitable. Trade settlement in yuan is expanding, particularly among Global South partners eager to bypass the dollar system.

Perhaps most striking is Beijing’s attempt to define itself as the global leader in the climate transition. While Washington resists binding commitments and under Trump has doubled down on fossil fuels, Xi Jinping’s government has pledged vast investments in renewables, electric vehicles, and “green finance.” At the United Nations General Assembly in 2025, Xi’s video address framed China as a responsible steward, a deliberate contrast with U.S. climate skepticism (Capital in Transition).

A Contest of Histories

The United States’ rise was sudden, concentrated in the twentieth century. The rise of China as global challenger is framed as a return — the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” by 2049, the centenary of the People’s Republic. Where America guards a fading crown, Beijing advances with the weight of history and the scale of demography.

As of 2025, the world is shaped by these dual narratives: a hegemon in relative decline and a challenger whose leaders insist they are not rising, but simply resuming their place in history.

References

- U.S. International Trade Commission (2022), Global Reliance on Chinese Manufacturing

- Reuters (2025), Foreign holdings of US Treasuries surge to all-time high in July, China’s sink

- NATO (2025), NATO Secretary General visits New York during UNGA, addresses West Point cadets

- Bureau of Labor Statistics (2025), Consumer Price Index

- Congressional Budget Office (2025), The Long‑Term Budget Outlook: 2025 to 2055

- Congressional Research Service (2018), The Marshall Plan: Design, Accomplishments, and Significance (R45079), Library of Congress

- Council on Foreign Relations (Education) (n.d.), The Marshall Plan

- Econofact (2024), U.S. Defense Spending in Historical and International Context

- International Monetary Fund (2025), World Economic Outlook (PPP shares of world GDP)

- Our World in Data (2024), Gross domestic product (Maddison Project Database; long‑run series)

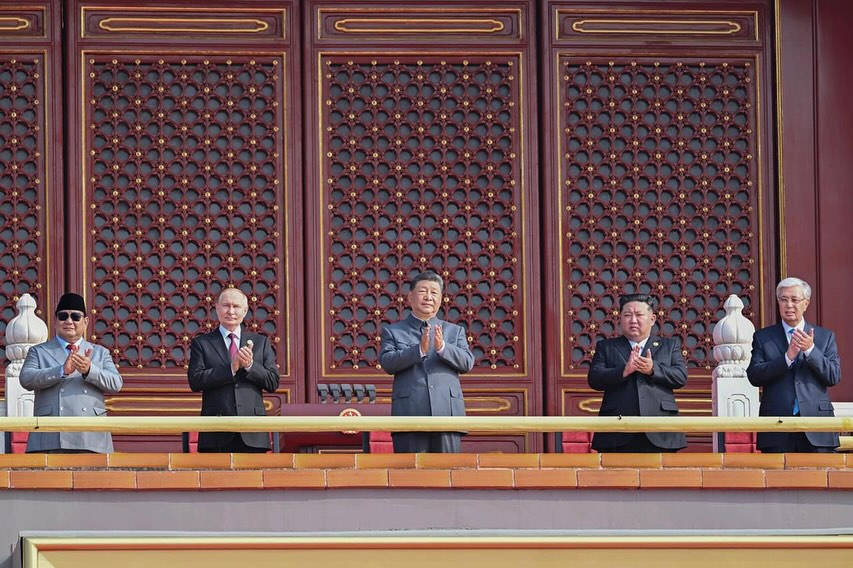

- Reuters (2025), China says Putin, Kim Jong Un to attend military parade

- Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (2025), Official website (English)

- The Guardian (2025), Xi Jinping says world faces “peace or war”, as Putin and Kim join him for military parade

- United States International Trade Commission (2019), Global Reliance on Chinese Manufacturing

- U.S. Geological Survey (2011) China’s Rare‑Earth Industry

- U.S. Treasury (2010), Report on Foreign Holdings of U.S. Securities at end‑June 2010 (TIC)

- World Bank (n.d.) GDP (current US$)

- St. Louis Fed (FRED) (2025), Gross Domestic Product for World (NYGDPMKTPCDWLD)

- France 24 (2025), ‘Kim and Putin join Xi Jinping at massive military parade in Beijing

- Al Jazeera (2025), China’s Victory Day military parade: who attended and why it matters

- Capital in Transition (2025), Zelenskyy’s Warning and China’s Climate Pledge

Archives

Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |