USA as Global Hegemon

The United States emerged from the Second World War in 1945 in a position no power had ever held before. Its homeland was untouched, its industries intact, and its armed forces deployed across every continent. Europe lay in ruins, Japan’s cities were razed, and the colonial empires of Britain and France were unraveling. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the U.S. accounted for an extraordinary share of global output (c. one-third to one-half, depending on the measure), a dominance visible in long-run GDP series compiled by the Maddison Project and the World Bank.

How the USA rose as global hegemon

Washington used this position to anchor a new international system. The dollar, fixed to gold at $35 per ounce, became the backbone of the Bretton Woods system, while the Marshall Plan transferred the equivalent of roughly $130–$200 billion in today’s money to Europe, binding recovery to American markets and capital. Institutions such as the IMF, World Bank, and NATO structured a world in which U.S. preferences became global norms.

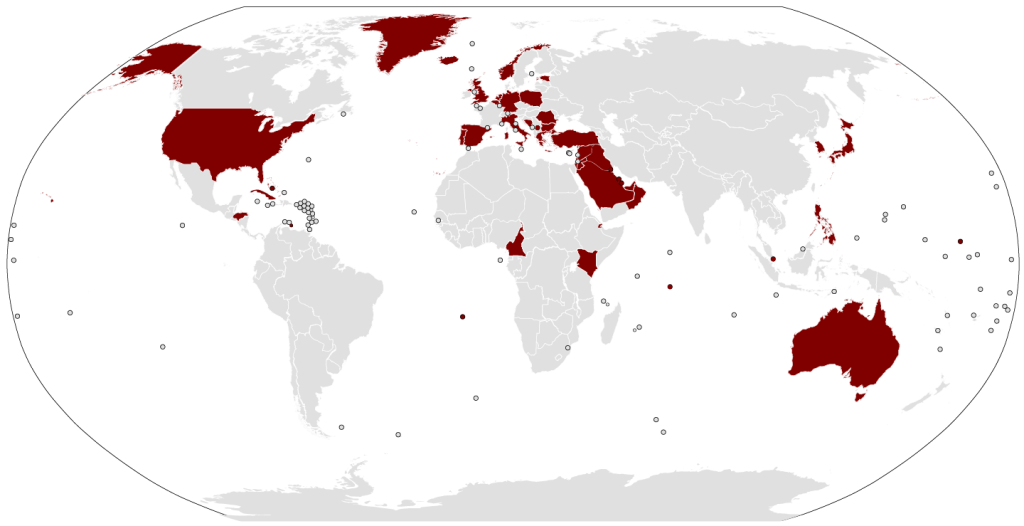

America’s military underpinned these arrangements. In the early Cold War and through the Vietnam era, defense outlays typically ran 8–10% of GDP (Econofact). A blue-water navy sailed across two oceans, and nuclear capability gave Washington commanding deterrence. Conflicts in Korea, Vietnam, and interventions across Latin America revealed both the reach and the limits of force, but the principle was clear: security flowed from Washington outward.

Through the 1960s, U.S. economic and technological dominance seemed unshakeable. U.S. output still sat near a third of the world economy by 1970 (World Bank). Detroit’s automakers led global production; companies such as IBM, Boeing, and General Motors set standards in computing, aerospace, and industry. The 1969 moon landing symbolized a technological lead that appeared unassailable.

When did supremacy begin to fray?

Strain appeared in the 1970s. The Vietnam War undermined confidence, the oil shocks of 1973–79 exposed dependence on foreign energy, and in 1971 the Nixon administration ended dollar–gold convertibility, shifting the system onto trust and U.S. financial depth rather than metal. Even so, the U.S. entered the 1990s in commanding position. The Soviet collapse (1991) left a unipolar world; the Gulf War demonstrated overwhelming precision weapons and logistics. Wall Street and Silicon Valley set the pace of the global economy.

The “tech wreck” of 2000–01 reminded investors of fragility: the Nasdaq fell nearly 80% wiping out trillions in paper wealth. Survivors like Amazon and Google went on to dominate. In 2001, China joined the WTO, accelerating the shift of manufacturing offshore. Over the 2000s, U.S. manufacturing employment fell by millions of jobs (BLS CES), while East Asia’s “flying geese” pattern matured—Japan, then Korea and Taiwan, and, increasingly, China moved up the value chain. By 2019 China accounted for about 28.7% of global manufacturing output versus 16.8% for the U.S. (USITC brief).

The Global Financial Crisis (2008–09) exposed systemic fragility. U.S. GDP contracted by over 4% in 2009; Washington injected emergency support and debt rose sharply. By 2010, China’s holdings of U.S. securities exceeded $1.6 trillion across asset classes, with about $1.1 trillion in Treasuries—underscoring the new creditor relationship.

Did new rivals emerge quietly?

The 2010s brought recovery, but also real challengers. China’s share of world GDP rose from roughly 2% in 1990 to the mid-teens by 2010 (IMF DataMapper). Beijing invested in Belt and Road infrastructure abroad and in renewables at home, while Washington leaned more on sanctions and export controls—especially around advanced semiconductors and equipment. Control of rare earths and other critical minerals concentrated outside the U.S., with China dominant in production and processing.

Then came COVID-19. Despite its wealth, the U.S. suffered over a million deaths, widespread shortages, and sharp political division. Congress approved about $5 trillion in emergency stimulus; public debt surged past 100–120% of GDP (CBO). Global supply chains buckled, with semiconductors and logistics bottlenecks halting factories. Inflation peaked at 9.1% year-on-year in June 2022 (BLS). By mid-decade, the cost of servicing federal debt was projected to exceed $1 trillion annually (CRFB).

Allies began to hedge. Europe rebuilt prosperity yet remained reliant on U.S. security guarantees. Russia, economically smaller but militarily potent, used force from Georgia (2008) to Ukraine (2022). India, courted as a counterweight to China, balanced among forums and partners. BRICS expanded and, on a PPP basis, amounted to roughly 40% of world GDP. The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) deepened Eurasian security coordination.

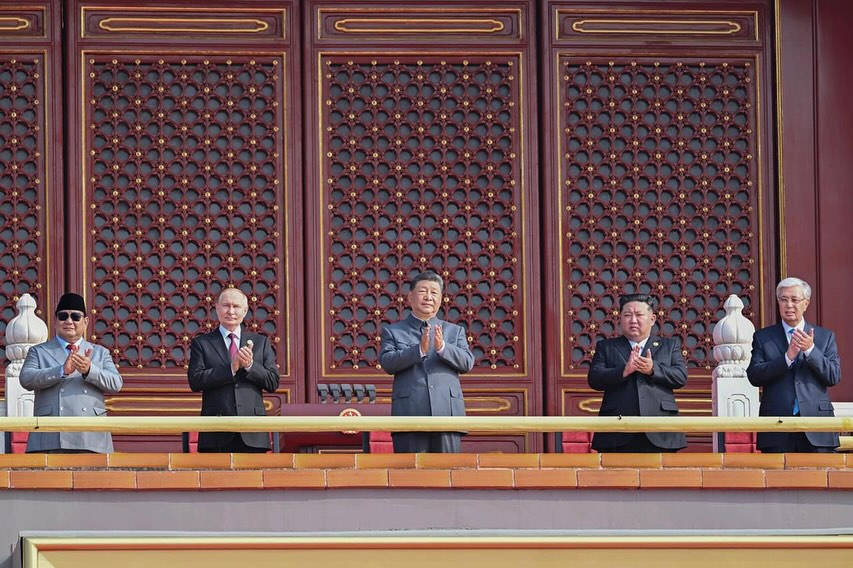

The symbolism grew unmistakable. In early September 2025, a Victory Day military parade in Beijing showcased hypersonic missiles and naval formations; Xi Jinping, Vladimir Putin, and Kim Jong-un appeared in close alignment (Reuters; France 24; Al Jazeera). At the United Nations General Assembly, Washington’s hesitancy on binding climate commitments contrasted with Beijing’s pledges on renewables.

In 1945, the U.S. accounted for an unparalleled share of global GDP. In 2025, it still produces about a fifth to a quarter of world output and leads in many technologies, with the dollar anchoring global finance (World Bank; IMF). Yet the pillars of hegemony—manufacturing depth, fiscal capacity, uncontested military reach, and cultural monopoly—are more strained than at any time since 1945. The unipolar moment has passed. The world is not yet post-American, but it is unmistakably post-unipolar.

References

- NATO (2025), NATO Secretary General visits New York during UNGA, addresses West Point cadets

- Bureau of Labor Statistics (2025), Consumer Price Index

- Congressional Budget Office (2025), The Long‑Term Budget Outlook: 2025 to 2055

- Congressional Research Service (2018), The Marshall Plan: Design, Accomplishments, and Significance (R45079), Library of Congress

- Council on Foreign Relations (Education) (n.d.), The Marshall Plan

- Econofact (2024), U.S. Defense Spending in Historical and International Context

- International Monetary Fund (2025), World Economic Outlook (PPP shares of world GDP)

- Our World in Data (2024), Gross domestic product (Maddison Project Database; long‑run series)

- Reuters (2025), China says Putin, Kim Jong Un to attend military parade

- Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (2025), Official website (English)

- The Guardian (2025), Xi Jinping says world faces “peace or war”, as Putin and Kim join him for military parade

- United States International Trade Commission (2019), Global Reliance on Chinese Manufacturing

- U.S. Geological Survey (2011) China’s Rare‑Earth Industry

- U.S. Treasury (2010), Report on Foreign Holdings of U.S. Securities at end‑June 2010 (TIC)

- World Bank (n.d.) GDP (current US$)

- St. Louis Fed (FRED) (2025), Gross Domestic Product for World (NYGDPMKTPCDWLD)

- France 24 (2025), ‘Kim and Putin join Xi Jinping at massive military parade in Beijing

- Al Jazeera (2025), China’s Victory Day military parade: who attended and why it matters

- Capital in Transition (2025), Zelenskyy’s Warning and China’s Climate Pledge

Archives

Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 |

| 30 | 31 | |||||